In all my years as a marine engineer I have, almost as a matter of course, specified that both manual and electric bilge pumps be used in any design that will likely see water enter the bilge from time to time. Sometimes this also extends to the freeboard deck if water can become trapped above the waterline, for instance in the case of a well deck.

Having said that, most of the vessels I have worked on have been ‘belt and braces’ military and commercial craft that have to adhere to every regulation under the sun, and then some. In the world of leisure boating, regulations often fall by the wayside, with much of what are perceived as ‘necessary safety precautions’ being left to the discretion of the boat owner.

So with that in mind I thought I’d throw in my two cents with regard to when bilge pumps are necessary, and other considerations with regard to the type used, their location on the boat and so forth.

An automatic bilge pump should be fitted to any vessel featuring a compartment that may get flooded, especially when the boat is unattended / where it may not be obvious water ingress is taking place. Manual bilge pumps are a secondary means of removing bilge water, but clearly serve no use when the boat is unattended.

No Need For a Bilge Pump?

Oftentimes the perception is that a hull that is watertight (below the waterline anyway) faces no risk of being filled with water, or worse sinking, as a result. If your boat falls into this category and you wish not to take the risk, then you must understand that by using the boat you are taking a healthy dose of just that, risk.

While in theory such a boat will not suffer the ills of water ingress, boating/sailing in the real world can of course be a very different experience. A GRP hull can suffer damage over time, whether the insidious creep of water seeping in through a crack and causing delamination, or the unexpected impact of a rock or some other obstacle tearing a hole in the side.

More commonly water can leak in through the packing gland of a prop shaft, or trickle down from the deck through hidden gaps and broken hatch seals.

Think about it, when you’re several miles offshore and such a disaster takes hold, you’re going to want all the help you can to get you out of trouble. I for one certainly wouldn’t feel comfortable travelling on board, let alone designing a boat without an adequate bilge system.

Where to Put The Pump?

Typical boat construction consists of a series of frames, some of which are sealed watertight bulkheads. For every compartment isolated by such bulkheads it is important to have a bilge pump.

The reasons for having compartmental separation between different areas include; providing a fire boundary (between an engine and fuel tank space for example), keeping bilge water from moving around too much and causing instability, but also to reduce the risk of flooding the entire vessel in the event of a hull breach.

Nonetheless, just because having only one compartment flood won’t result in the entire vessel sinking, doesn’t mean you shouldn’t try to keep the water out altogether.

A flooded compartment could prevent you from making your way back to shore, or at the very least result in a lot of expensive damage.

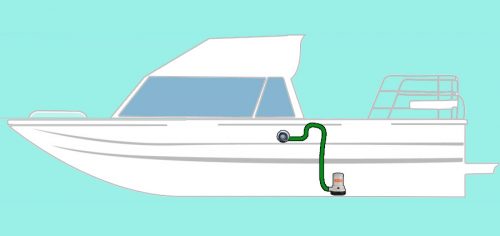

Positioning your bilge pump in each compartment, simply involves mounting the strainer or strum box at the lowest point. If you don’t do this, puddling could still occur below the point you have mounted the strainer.

It is important to include a non return or ‘check’ valve in each bilge line so that there is no back flow of water into the bilge when pumping is halted.

Manual, Automatic or both?

We know that having an automatic bilge pump gives you the extra security of not having to be around or even aware of a leak when it becomes a problem, but having a manual pump is still a useful backup, especially in emergency situations.

The gold standard manual bilge pump has to be the ‘Gusher’ by Whale. I’ve honestly seen this on more boats than I haven’t, and there is little dispute over its efficacy.

To save space and reduce the number of bilge outlets required it is a good idea to use a ‘Y’ or ‘T’ piece and have the two bilge lines converge to single skin fitting.

Spare Bilge Pumps?

Of course having an automatic bilge pump in each compartment is far, far better than having none at all. However electrical systems are prone to failure at the worst possible time, therefore having a redundant system is a very good idea.

The key consideration when installing a backup automatic bilge pump is to mount it slightly higher than the primary pump. This is to ensure the backup pump doesn’t fall foul to any obstructions or sludge at the lowest point in the bilge that have caused the primary pump to fail.

Parts of The Bilge System Required

Strainer/Strum Box

This device is mounted at the lowest point in the hull and is the point at which bilge water enters the hose to be pumped out. The strainer has a grate on it to filter out any large debris prior to pump out.

It’s important to pay periodic attention to the strainer to ensure no debris has become lodged within it, as this will greatly reduce the performance of the pump, which could be catastrophic at the wrong time.

Many self priming pumps have the stainer built into the pump unit and therefore don’t require an additional strainer.

Float Switch

In an automatic bilge pump something is required to trigger the pump to begin operating. This is where a float switch comes in.

As the name suggests, the floating element of a float switch floats, therefore when water gets underneath it, it floats upward and triggers the electric motor in the pump to begin operating.

Likewise once the water level drops, the switch will drop back down, switching the pump off.

Bilge hose

Most pumps have a hose inlet/outlet size of between ¾” and 1 ½” with many having a spigot that allows for 2 different hose sizes.

Hoses are typically held in place with stainless steel hose or ‘Jubilee’ clips. As best practice I usually fit 2 clips to each hose connection point.

The hose you should choose can be any marine grade water or fuel hose. Again be sure to routinely check the hose for signs of wear and tear.

Bilge Pump

As mentioned above the whale gusher is more or less the go to option for manual bilge pumps, but for automatic pumps the options are more varied.

There two main types of bilge pump: self priming and non self priming.

Whilst non self priming bilge pumps are cheaper and simpler (and therefore less likely to malfunction). However, as the name suggests, a non self priming pump will not run without water in the impeller chamber, therefore the pump must be submerged in order to work.

Their simplicity, and the fact they will inevitably become submerged in the event of primary pump failure makes non self priming pumps suitable as a backup bilge pump.

Self priming pumps don’t need to be submerged to run, instead sucking in small amounts of water as soon as their float switch is triggered.

As far as sizing goes, the more water you can shift the better, but obviously you need to consider size and weight when choosing a suitable pump for your boat.

Check valve

Again, a non return valve needs to be present in every bilge line, upstream (in the direction of pump) of the pump. These should also be attached with 2 jubilee clips on each hose connection.

Skin fitting

This is the outlet mounted to the hull outer skin.

These are usually available in stainless steel, plastic and GRP. Whilst more expensive, a stainless steel skin fitting will be longer lasting, and may suffer less against sun damage than the plastic and composite varieties.

Bilge Alarm

It can be very useful to have an indication at the helm when the automatic bilge system has kicked in.

A bilge alarm panel can be wired into the vessel along with the automatic bilge pump, or with more sophisticated software systems aboard, the alarm can be programmed to show an alert on the conning display.